Read the Report

Home / Read the Report

Section 5: Recognizing, Responding to, and Reporting Allegations and Suspicions of Child Sexual Abuse

Executive Summary

Although this report is focused on the prevention of child maltreatment and raising awareness among YSOs about the steps that can be taken to create and strengthen the youth serving environment to protect the children in their care, YSO personnel must also be ready to recognize child abuse when it occurs and to respond to it immediately, appropriately and effectively.

In the introduction to this report, the statistics for the various forms of child abuse and neglect in both the United States and in Massachusetts are presented in summary form. Given these numbers, it is certainly within the realm of possibility that no matter how large or small a YSO is, at least some of the children and youth participating in, or receiving services from its programs could have been, are, – or may be at risk to become – victims of sexual abuse and human trafficking 1 . This is not to say that every YSO in Massachusetts definitely has children or youth in these circumstances – only that it is possible. And if it is possible, then every administrator, manager, supervisor, employee and volunteer should be able to recognize what it looks like, how to respond to it, and how to get them the help they need to make it stop.

Affording the maximum protection for children and youth requires YSOs to increase staff and volunteer awareness about child abuse, to train them to recognize a child who may be in trouble, and to inform them about their responsibilities under the Massachusetts reporting laws and the policies and procedures of the YSO. Leadership must then support the staff in those responsibilities and actions by creating a culture where child safety and abuse prevention are a priority; where all staff and volunteers are encouraged to come forward; where concerns about behaviors can be expressed and discussed without fear; and where immediate and appropriate action is taken to respond to the child/youth, and to report the allegation, suspicion, or disclosure to the people and organizations responsible to respond.

In the Code of Conduct section above, the Task Force addressed the importance of establishing in writing the expected behaviors of staff and volunteers when supervising or interacting with children and youth. Further, the section emphasized training, education and ongoing conversations and supervision about defining and understanding the differences between appropriate, inappropriate and harmful behaviors, and establishing clear lines of communication, reporting, and the actions to be taken should any staff or volunteer witness an event, interaction or situation that falls outside of the boundaries of appropriateness. In this way, inappropriate behaviors or boundary violations with children and youth that were inadvertent or due to inexperience can be addressed through intervention, supervision, and monitoring – and corrected before they cross the line into harmful or abusive behaviors that must be reported.

Similarly, in the Introduction to this report, the symptoms – both behavioral and physical – that children and youth exhibit when being subjected to various types of physical, emotional and sexual maltreatment were outlined. For convenience, they are repeated in chart form below. The behavioral characteristics of the grooming process were also described to point out the warning signs that indicate an offender may be preparing a child or youth for eventual sexual contact. Again, if all staff and volunteers understand and conform to the Code of Conduct, it makes the behaviors of those who do not feel the rules apply to them easier to notice.

In addition to recognizing the symptoms of the various types of abuse, YSO staff may become aware that a child is being maltreated or abused because another child, or another adult points out the symptoms or otherwise indicates that a child is at risk. In still other circumstances, the child may self-disclose the alleged abuse – either directly to a YSO adult, or indirectly by describing the situation as happening to “a friend” and asking the adult for advice.

This section focuses on the situations where a staff member/volunteer in a YSO suspects or has evidence that a child or youth is a victim of abuse – particularly sexual abuse or human trafficking/sexually exploited child – and what the individual, his or her supervisors, and the YSO must do in response. It also explains the Massachusetts mandatory reporting laws, how to make a report to the Department of Children and Families (DCF), and DCF’s responsibilities and possible responses. The section also addresses more specifically the circumstances and resulting actions that should occur when the alleged abuse is being perpetrated by someone within the YSO – either by an adult staff member or volunteer, or by another child/youth. Finally, the section addresses the emerging issue of child trafficking and some of its unique characteristics. Minimum required elements for YSOs to prepare leadership, staff and volunteers to recognize, respond to, and report allegations, suspicions or disclosures of child abuse are presented below in Table 6, and an implementation and decision making model for how YSOs of various size can access and meet those requirements follows.

| Table 6 |

| Minimum Required Elements for Recognizing, Responding to, and Reporting Child Abuse |

| ✔ | All Employees and Volunteers: |

| Are aware of their legal/organizational obligations to immediately report suspected abuse. | |

| Are trained to recognize the signs and symptoms of abuse. | |

| Know how to respond to a child who discloses abuse. | |

| Know how to report concerns, suspicions, allegations and disclosures of abuse. | |

| Other Required Elements: | |

| Clear, written procedures that provide step-by-step guidance on what to do if there are any concerns, allegations, suspicions or disclosures of abuse (current or historic). | |

| A designated person (agent)/group/office whose role it is to receive reports of suspected, observed or disclosed abuse. | |

| A clear reporting chain is identified that contacts (or assists reporters in contacting) DCF and/or law enforcement. | |

| Clear guidelines on conducting internal investigations when the alleged perpetrator is an employee or volunteer in the YSO. | |

| Clear guidelines about reporting that include providing supervision and support to staff and volunteers following an incident or allegations, and a communication plan for parents/community. | |

| Information/training about the issues of child and human trafficking. |

Key Findings and Recommendations

- In addition to building a prevention structure that proactively works to protect children and youth from sexual abuse, YSOs must also work to prepare staff and volunteers to recognize, respond to, and report abuse that is alleged, suspected or disclosed.

- YSO staff and volunteers must be trained to recognize the signs and symptoms of abuse.

- Maximum protection for children and youth requires YSO leadership and staff to be familiar with the Massachusetts child abuse reporting laws, the offices and numbers to call, the timeframes involved, and the 51A reporting form.

- YSO Policies and Procedures and Codes of Conduct should include the state’s reporting requirements and clearly state that the YSO expects all staff and volunteers – mandated or not – to immediately report any suspicions, allegations, or disclosures of child abuse.

- YSO leadership should identify an individual, a team, or department that will act as a designated agent to talk with staff about any concerns, receive reports of alleged abuse, and either make contact with DCF or assist the reporter in doing so.

- YSOs need to “normalize” reporting as a requirement and support staff and volunteers in their responsibilities. Reporting chains must be clearly defined.

- All YSO employees and volunteers should know how to respond to a child/youth who discloses an abusive situation and YSO policies and procedures should have clear guidance on the steps to follow if this occurs. Guidance and sample flow charts are provided.

- Knowing what happens when a report is made to DCF and the legal protections for reporters can help “demystify” the process and reduce staff reluctance to come forward.

- Reports of alleged sexual abuse involving YSO staff, volunteers or even other YSO children/youth will require additional internal reporting structures, investigation (limited), notification to parents, and communication planning.

- The emerging area of child trafficking requires YSOs to be aware of the additional signs and symptoms of commercially exploited children, and the resources available should it be suspected.

Recommended Implementation and Decision Making Model

STEP 1 – RECOGNIZE: Determine and implement appropriate ways to inform YSO staff and volunteers about the signs and symptoms of child abuse and neglect, and make them aware of their responsibilities under Massachusetts law.

- Introduce to prospective staff and volunteers during the screening and hiring process that the YSO, in addition to providing its services, strives to provide those services in an environment that is safe and that responds immediately to allegations, suspicions or disclosures of child abuse.

- Include in the YSO’s Policies and Procedures and Code of Conduct the requirement for all staff and volunteers to report any allegations, suspicions or disclosures of child abuse.

- Use the information in this section on the Massachusetts definitions of child abuse, the Chart on Physical and Behavioral Indicators of Abuse/Child Trafficking (below), the DCF Reporting Brochure and the Sample Reporting Flow Chart in Appendix 11 as handouts to introduce the facts about child abuse and its symptoms.

- Keep focus on answering the basics: “What is child abuse?” “How do I recognize it?” and “What am I supposed to do when I see it?

- Depending on size and number of employees and volunteers, YSO leaders can consider conducting roundtable discussions, “brown-bag” lunches, in-service training or “professional days” on the topic of child/youth safety.

- Consider assigning online training modules to be completed; partnering with other YSOs already conducting training programs; or inviting DCF or other local social service agencies to conduct an on-site workshop or training (Also see Training section).

STEP 2 – RESPOND: Determine the process by which the YSO will prepare staff and volunteers to respond to a child/youth who discloses abuse. Consider ways to encourage and support staff in coming forward to report child abuse that is suspected, observed, or disclosed.

- Teach staff and volunteers that the way a disclosure of child abuse is handled can affect the impact it has on the victim.

- Reproduce and use the Guidelines for Disclosures below to discuss the ways to respond to children and youth who disclose abuse so that they feel supported and believed.

- Ensure that whoever is talking with staff and volunteers about these topics is comfortable with the subject matter. These are not easy conversations to have, but they are critical – not taboo. The comfort of the presenter can affect the comfort of staff and volunteers.

- Maximize opportunities to talk with staff about child/youth protection issues and policies. Regular conversations will make it easier for staff to discuss behaviors, ask questions and approach situations from a prevention perspective.

- Ensure that staff knows that reporting suspected abuse (even if the reporter is unsure) affords protections for the reporter under Massachusetts law. The protection of the victim is the primary concern. Reluctance to come forward and report is often a result about concerns of personal liability.

STEP 3 – REPORT: Determine the YSO responses to allegations, suspicions and disclosures of child abuse committed by individuals outside the YSO, and by YSO staff or volunteers. Include the specific cases of suspected child-on-child or youth-on-youth abuse, and child trafficking.

- Staff must understand the steps to follow in making a report – and to whom the report must be made.

- In simplest form, a YSO can choose to designate a single person or “officer” to whom all reports are made. The designated reporter then assumes the responsibility (or helps the reporter) to contact the authorities, provide the required information, and follow up with the filing of the 51A Report Form (See Appendix 11).

- Ensure the reporting chain is clearly described. In smaller organizations, the reporting chain could be a single person. In larger organizations, the chain could include supervisors, managers, human resources, communications and legal staff.

- Provide forms that will make it easier for incidents to be recorded by staff and ensure the confidentiality and security of those records (see Sample Incident Report).

- If the offender is a YSO staff member or volunteer, an additional internal reporting and investigation process will likely need to happen concurrent with the DCF response. This includes:

- Interviewing the alleged offender and informing them of the allegations

- Determining the employment status of the alleged offender

- Coordinating with DCF the response to the victim and family

- Notifying the rest of the staff and providing support

- Assessing the conditions that allowed for the abuse to occur

- Preparing a response to other parents, and to the media

- Make staff and volunteers aware that problematic sexual behaviors or abuse can also take place between children or youth, and that children/youth also exhibit the symptoms of being sexually exploited or trafficked. In either case the process is the same – report to the designated reporter and contact DCF.

- These processes should be identified in the YSO’s policies and made clear to all staff and volunteers.

Goal

To respond quickly and appropriately to allegations, suspicions, observations or disclosures of child sexual abuse.

General Principles

Organization leadership can help to build and maintain an environment in their YSO that is preventive and proactive in nature – that protects children either by preventing child abuse before it occurs, or by ensuring its detection at the earliest possible time. They can also help to ensure that all employees and volunteers understand the basic issues of child abuse and neglect; how to recognize its signs and symptoms; are familiar with Massachusetts law, policies and reporting procedures; and know the responsibilities of mandated reporters including how, when, and to whom to make a report. These will be covered first in this section, and will be followed by suggestions about how YSOs of various size can address these requirements, how to react to a child who discloses abuse, and the different circumstances YSO personnel may encounter that require reporting – including situations where a child or youth is being harmed or abused by another child or youth with problematic sexual behaviors.

The bottom line is that YSOs need to build and sustain an organizational mindset or culture such that if child maltreatment is suspected, observed, or disclosed to any member of the staff, that person will come forward with their concerns as quickly as possible, will know what to do to ensure the child’s safety and well-being, will communicate the situation promptly and effectively to the person(s) identified in the YSO’s Code of Conduct and, if necessary, will know how to report the circumstances to the Department of Children and Families (DCF) or to the police. Early reporting is critical and is the key to preventing further harm.

Massachusetts State Law

Mandated reporters are required to immediately report suspicions of child abuse and neglect to the Massachusetts Department of Children and Families (DCF) by phone, followed by a written report (called a 51A) within 48 hours, when in their professional capacity they have “reasonable cause to believe that a child is suffering physical or emotional injury resulting from: (i) abuse inflicted upon him which causes harm or substantial risk of harm to the child’s health or welfare, including sexual abuse; (ii) neglect, including malnutrition; (iii) physical dependence upon an addictive drug at birth, or (iv) human trafficking – sexually exploited child; or (v) human trafficking – labor 2 as defined by section 20M of chapter 233” (Mass. General Laws 3 ).

The law states further that “If a mandated reporter is a member of the staff of a medical or other public or private institution, school or facility, the mandated reporter may instead notify the person or designated agent in charge of such institution, school or facility who shall become responsible for notifying the department in the manner required by this section. A mandated reporter may, in addition to filing a report under this section, contact local law enforcement authorities or the child advocate about the suspected abuse or neglect.” Mandated reporters who fail to report can be punished by fines of up to $1,000.

It is important to note that the language above requires the reporting of suspected abuse to DCF. No state, including Massachusetts, requires the reporter to have conclusive proof that the abuse or neglect occurred before reporting. Reporters are not expected to be investigators. The law clearly specifies that reports must be made when abuse is observed, or the reporter “suspects” or “has reasonable cause to believe” that a child has been or is being harmed. Asking the child too many questions, or for greater detail in order to feel more confident before filing a report may confuse or re-traumatize the child, convey a sense to the child that they are not believed, or – in the worst case – cause the child to stop talking altogether. The job of investigation should be left to the professionals at DCF and law enforcement who are trained in interviewing children and youth who have been victims of trauma. In all cases the intent is clear: incidents are to be reported as soon as they are noticed or suspected. The benefit of the doubt is always given to the suspected victim. Waiting for conclusive proof may put the child or youth at further risk.

Mandated reporters are also protected under the law. If the report is made in good faith, mandated reporters are protected from liability in any civil or criminal action and from any discriminatory or retaliatory actions by an employer – even if the report is deemed unfounded after investigation. The name of the reporter is not disclosed by DCF to the parents/guardians of a child who is the subject of the report.

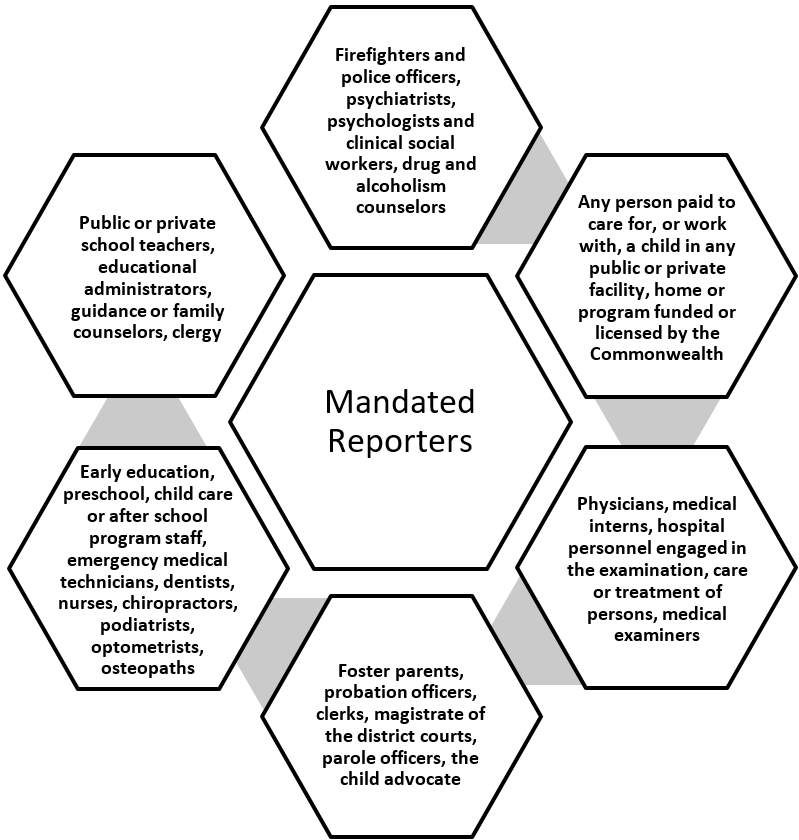

Who are Mandated Reporters?

Massachusetts law defines a number of professionals as mandated reporters (for the full list see MGL Chapter 119, Section 51A):

A Sampling of Massachusetts mandated reporters*

*As of January 1, 2020

Note that the list of mandated reporters above identifies professionals and other paid staff employed by certain organizations in a variety of roles. However, there is nothing in the law that prevents anyone from making a report. Thus, while acknowledging the role of statutory mandated reporters in their policies and procedures, YSOs – even those who do not employ mandated reporters – should express the expectation in their policies that all staff who interact directly with children and youth (including volunteers and other non-mandated reporters) are required to report any suspected child abuse or neglect, or any situations involving inappropriate activity with a child/youth, and will be trained in the procedures to do so. There is more detail on training structures and programs in the Training section below.

Further, it is recommended that YSO Codes of Conduct should include the requirement for all staff and volunteers to follow the reporting laws of the Commonwealth and the organization, and declare by means of their signature that they understand the penalties for failing to do so – up to and including dismissal. Non-mandated reporters are accorded the same protections under the law as mandated reporters 4 (see Policies and Procedures, Code of Conduct, and Training sections in this report).

Recognizing Abuse and Neglect

What are the signs and symptoms of abuse and neglect?

The definitions in Massachusetts law of the various types of child maltreatment, and the physical and behavioral signs that indicate a child/youth may be suffering from abuse have been defined above (see Introduction). But it is important to note here that child abuse, especially child sexual abuse, is rarely observed directly. There are usually three ways in which a potential reporter might recognize that a child is being abused:

- The child/youth demonstrates certain physical or behavioral symptoms;

- Another child, youth or adult indicates that a child/youth is at risk; or

- A child/youth self-discloses the abuse

In the absence of direct disclosure by the child or youth, or communication from another person that a child/youth is at risk, one must rely on the signs and symptoms that children and youth exhibit when they are victims of abuse and neglect. Although these have been discussed in the Introduction above, they are summarized here in chart form for re-emphasis and convenience:

Physical and Behavioral Indicators of Abuse 5

| Type of Abuse | Physical Indicators | Behavioral Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Abuse | ● Unexplained bruises (in various stages of healing) ● Unexplained burns, especially cigarette burns or immersion burns ● Unexplained fractures, lacerations or abrasions ● Swollen areas ● Evidence of delayed or inappropriate treatment for injuries | ● Self destructive ● Withdrawn and/or aggressive – behavioral extremes ● Arrives at school early or stays late as if afraid to be at home ● Chronic runaway (adolescents) ● Complains of soreness or moves uncomfortably ● Wears clothing inappropriate to weather, to cover body ● Bizarre explanation of injuries ● Wary of adult contact |

| Neglect | ● Abandonment ● Unattended medical needs ● Consistent lack of supervision ● Consistent hunger, inappropriate dress, poor hygiene ● Lice, distended stomach, emaciated ● Inadequate nutrition | ● Regularly displays fatigue or listlessness, falls asleep in class ● Steals food, begs from classmates ● Reports that no caretaker is at home ● Frequently absent or tardy ● Self destructive ● School dropout (adolescents) ● Extreme loneliness and need for affection |

| Sexual Abuse | Sexual abuse may be non-touching (obscene language, pornography, exposure) or touching (fondling, molesting, oral sex, intercourse) ● Torn, stained or bloody underclothing ● Pain, swelling or itching in genital area ● Difficulty walking or sitting ● Bruises or bleeding in genital area ● Venereal disease ● Frequent urinary or yeast infections | ● Excessive seductiveness ● Role reversal, overly concerned for siblings ● Massive weight change ● Suicide attempts (especially adolescents) ● Inappropriate sex play or premature understanding of sex ● Threatened by physical contact, closeness |

| Emotional Abusemmmm | Emotional abuse may be name-calling, put-downs, etc. or it may be terrorization, isolation, humiliation, rejection, corruption, ignoring ● Speech disorders ● Delayed physical development ● Substance abuse ● Ulcers, asthma, severe allergies | ● Habit disorder (sucking, rocking, biting) ● Antisocial, destructive ● Neurotic traits (sleep disorders, inhibition of play) ● Passive and aggressive – behavioral extremes ● Delinquent behavior (especially adolescents) ● Developmentally delayed |

What to Do

In General…

With some exceptions, a single incident or observation of any of the above may not necessarily trigger the need for a call to DCF. However, if an indicator is observed, and a decision is made not to contact DCF, it should be a red flag to maintain a watchful eye on the child or youth, confer with fellow staff or supervisors as to whether they have noticed similar physical and/or behavioral symptoms, and keep notes about the behaviors that are causing concern. Certainly, if a pattern emerges, or the symptom becomes more pronounced or severe, a call to DCF must be made.

Most people have never filed a report with DCF, and many people – especially non-professionals – who work or volunteer with children or youth may feel a certain reluctance to do so. Questions about personal liability, being sued, causing trouble to another family or to their employer, mistrust of the authorities like DCF, not knowing exactly what will happen after a report is made, or just the possibility of being wrong may be enough for someone to start “second-guessing” the situation or their own observations and reactions and remain silent. YSO leaders need to take steps to address this reluctance by “demystifying” the reporting process, by showing staff and volunteers that they will be supported in their efforts to keep children and youth safe, and that there will be no negative consequences or repercussions for reporting – even if the report turns out to be wrong.

In addition to the institutions mentioned specifically in the 51A law, any YSO may identify a “designated agent” or individual to receive reports of suspected abuse from staff and volunteers. In this way, staff who believe they have information or observations that indicate a child or youth is at risk have someone to speak with and, as a result, can feel less isolated and vulnerable. In small, single proprietor YSOs with a limited number of employees, owners can designate themselves as the person to whom all reports or suspicions should be communicated. In larger organizations, it could be a supervisor, or the head of a department, the principal of a school, a guidance counselor or even a small multidisciplinary team.

NOTE: It may happen that the designated agent does not agree with the reporter that the situation being brought forward warrants a call to DCF. The fact that this may happen should not prevent a reporter – especially a mandated reporter – from contacting DCF directly if he or she remains convinced, and has reasonable cause to believe that the suspected abuse or neglect did occur. The YSO should also make it clear that it will not discharge or in any manner retaliate or discriminate against any person who, in good faith, submits a report of child abuse or neglect to DCF.

However, the individual or team identified as the designated agent or reporter should be familiar with the local DCF office, with the procedures that need to be followed to make a report, and with what happens once a report is filed. In this way, the person or group “teams” with the reporter, knows what DCF will be looking for in terms of information, knows whom to contact and ask questions, and provides an informed “sounding board” that can help the reporter and YSO take the next steps to protect the child or youth.

To increase awareness among staff and volunteers, YSOs can maintain in abbreviated form, as an appendix to their Policies and Procedures, or as an attachment to their Code of Conduct, instructional materials about child abuse (e.g., the chart above on physical and behavioral indicators) and a 1-page flow chart of the sequence to follow, the people to contact and the numbers to call if abuse is suspected, observed or disclosed (See sample charts in Appendix 11).

YSO leaders can use these materials as part of the orientation process for new hires or volunteers, and include them in annual training or professional development efforts.

Larger organizations may also develop or purchase commercially available onsite and online training programs tailored to their specific environments. In some cases, insurers have developed child abuse prevention and reporting education programs as part of their client risk mitigation programs. There is also a publicly available training resource for mandated reporters offered by the Middlesex District Attorney’s Office at (http://51a.middlesexcac.org). Abuse prevention training programs – including personal safety training programs for children and youth – will be discussed in more detail in the Training section below.

Since the vast majority of abuse cases – including incidents of sexual abuse – take place at the hands of someone a child/youth knows and trusts, most of the situations that will come to the attention of YSO personnel will likely be situations occurring outside of the YSO – in the home, or within the extended family, or the family’s social network. In other cases, however, the allegation may concern a current or past employee or volunteer of the YSO or even another child or youth attending a YSO program. In the latter two instances, additional guidance will need to be drafted that includes the process of internal investigation, notification to parents and a plan for public communication and response. These will be addressed in more detail below.

Responding to a Direct Disclosure

Sometimes, a child or youth might self-disclose an abusive situation to an adult in the organization. These disclosures can be direct, where the child or youth self-identifies as the victim, or more indirect where the child/youth describes the situation as though it is happening to someone else and is asking for advice about helping the “friend”.

Faced with an abuse disclosure by a child or youth, anyone might feel at a loss as to what to say. First, it is vital to communicate several things to them: that you are very glad that they told you, that you believe them, and that they are not to blame. Whether or not you believe the story that the child/youth has told, they have told you for a reason. Until you know why, the child/youth must feel believed (the number of false reports by children/youth are negligible). Research indicates that the adult response to a child’s/youth’s disclosure can have an impact on their recovery. It may also help the child if you communicate that this happens to other children, and they are not alone. Of course, a direct disclosure from a child/youth requires an immediate report to DCF and/or to law enforcement or the Child Advocate. The following are some additional tips that will be important in talking with the child:

Guidelines for disclosures

- Do not let the child/youth swear you to secrecy before telling you something. You may need to report.

- If a child/youth asks to speak with you, try to find a neutral setting where you can have quiet and few interruptions.

- Do not lead the child/youth in telling their story. Just listen, and let them explain what happened in their own words. Do not pressure them for a great amount of detail.

- Respond calmly and matter-of-factly. Even if the story is difficult to hear, it is important not to register disgust or alarm.

- Avoid making judgmental comments about the abuser. It is often someone the child or youth loves or with whom they are close.

- Children/youth often feel (or are told) that they are to blame for their own maltreatment and for bringing “trouble” to the family; therefore, it is important to reassure children and youth that they are not at fault.

- Do not make promises to the child/youth that things will immediately get better. In reality, things may get worse before they get better, but conveying this to the child or youth may cause greater anxiety.

- Do not confront the abuser. This may cause more harm to the child/youth.

- Ask the child/youth if they feel safe going home. If they do not, or if you believe that it isn’t safe for the child/youth to return home, this should be considered an emergency and handled immediately by contacting DCF and/or the local police department. Do not take the situation into your own hands. Provisions for the child’s/youth’s safety should be made by an appropriate agency.

- Respect the child’s/youth’s confidence and limit the number of people with whom you share the information. The child’s/youth’s privacy should be protected.

- Explain to the child/youth that you must tell someone else in order to get some help. Try to let the child/youth know that someone else may also need to talk with them and explain why.

- Assure the child/youth that you or another staff member will be available for support whenever possible. 6

Remember that children and youth who disclose are often frightened or anxious and will need reassurance, encouragement, and support throughout the weeks to come. DCF staff can help guide everyone concerned about how they might provide this support.

Should the child’s parents be notified about the intention to report?

The issue of how and when to involve parents, especially if it is the parents who are suspected of the abuse or neglect, is always difficult. If the family is told before DCF gets involved, it is always possible that the child could be further harmed before any protection is in place. Although families will sometimes remove children from the organization or flee the area, professionals argue that a family who is told that a report is being made can also be helped to recognize that reporting is a helping rather than a punitive gesture. If the YSO has a good relationship with the family, this is especially true. However, it is characteristic of abusive and neglectful families to isolate themselves and that makes it more difficult to predict how they will react to a report to the authorities. When in doubt, it would be best to call DCF and ask for their direction. The bottom line is that the immediate protection of the child or youth must always be the primary concern.

Reporting suspected child abuse

When YSO staff suspect that a child is being abused and/or neglected, they are required to immediately telephone the local DCF Area Office and ask for the Screening Unit. A directory of the DCF Area Offices and a copy of the 51A report form, can be found in Appendix 11 and on the DCF web site. 7 Offices are staffed between 9 am and 5 pm weekdays. To make a report at any other time, including after 5 pm and on weekends and holidays, call the Child-At-Risk Hotline at 800-792-5200. Reporters are also required by law to mail or fax a written report to DCF within 48 hours after making the oral report.

The DCF Protective Intake Policy is divided into two phases: (1) the screening of all reports; and (2) a response to any report that is screened in. All screened-in reports are now investigated. A detailed description of what happens when a report is made to DCF, and a description of the investigative process, its timelines, and a step-by-step chart appear below in Appendix 11.

When the call is made, and when filling out the 51A form, the reporter should be prepared to provide the following information, if known:

- Your name, address and telephone number, and your relationship (if any) to the child(ren)/youth.

- All identifying information you have about the child/youth and parent or other caregiver, and information about other children/youth in the household if known.

- The nature and extent of the suspected abuse and/or neglect, and/or human trafficking/sexual exploitation or labor, including any evidence or knowledge of prior injury, abuse, maltreatment, or neglect.

- The identity of the person(s) you believe is/are responsible for the abuse and/ or neglect.

- The circumstances under which you first became aware of the child’s/youth’s injuries, abuse, maltreatment or neglect, and/or human trafficking/sexual exploitation or labor.

- What action, if any, has been taken thus far to treat, shelter, or otherwise assist the child(ren)/youth.

- The child’s/youth’s visibility within the community (e.g., child care, school attendance. etc.).

- Emergency contact information for the children/youth being reported, and languages spoken in the household.

- Any concerns about alcohol, drug use, misuse by the parent/caregiver.

- Any other information you believe might be helpful in establishing the cause of the injury and/or person(s) responsible, any concerns you have for social worker safety.

- Any information that could be helpful to DCF staff in making safe contact with an adult victim in situations of domestic violence (e.g., work schedules, place of employment, daily routines).

- Any other information you believe would be helpful in ensuring the child’s/youth’s safety and/or supporting the family to address the abuse and/or neglect concerns (other contributing or high risk factors, the family’s strengths and capacities, etc.).

NOTE: IF YOU DO NOT HAVE ALL THIS INFORMATION, DO NOT LET THIS KEEP YOU FROM FILING. FILE WITH WHAT INFORMATION YOU DO HAVE AND LET THE PROFESSIONALS MAKE THEIR DETERMINATIONS.

What if the abuse is being perpetrated by someone within the organization?

It is extremely disturbing for most adults to consider that a colleague or co-worker might be abusing children – but it happens. In these cases, however, children need special protection. A common response when a fellow employee or volunteer is suspected of abuse, especially if the person is popular or has been part of the organization for a long period of time, is to deny, rationalize, or ignore it. Sometimes the alleged abuser is transferred to another organizational location, is allowed to resign, or is fired. But experience has shown that, even with a suspension, reprimand or transfer, the violation is likely to recur in the absence of intervention and monitoring.

Again, Codes of Conduct exist to clearly identify a range of expected and prohibited behaviors for all adults who interact with children and youth. If an employee or volunteer is behaving in a way that causes concern, it would be important for the observer to be able to distinguish violations of the Code that require a report to law enforcement or DCF, from those that may be handled organizationally (e.g., are correctable by supervisors or managers). Employees and volunteers – even those who are not mandated reporters – should be required to address or report any behaviors and practices that may be inappropriate or harmful. Inappropriate behaviors or minor violations of the Code can sometimes be addressed by a fellow employee who brings the violation to the attention of the offending co-worker in order to remind him or her of the rules. If the behaviors persist, however, reporting them to a supervisor or manager for correction would be more appropriate. If the behavior is more serious and raises suspicion that a child or youth is about to be, or is being abused, a report to DCF must be made.

If a child/youth reports being sexually, physically, or emotionally abused by someone in the organization, we should remember that it takes courage for an abused child or youth to talk to someone. After using the guidance above to talk with them, the best course of action for the YSO is to immediately report the disclosure to DCF. DCF personnel then interview the child/youth or refer the allegations to law enforcement (depending on the situation) to determine the veracity of the allegation. If the child or youth knows anyone else to whom this has happened, a 51A report is required by the mandated reporter, and the DCF investigator will likely wish to talk with any other alleged victims.

In the situations where DCF is contacted and begins its investigation, there will also likely be an organizational reporting chain to be notified. Depending on the size of the organization, this internal chain could include human resources, supervisors, organization leadership, the risk management and communications office and the general counsel – possibly even the Board of Trustees. Their tasks might include interviewing and notifying the alleged offender of the allegations, determining whether the alleged offender should be placed on leave (with or without pay) or fired, notifying the rest of the staff, communicating with parents, press releases to notify the general public, determining whether it is safe for the child/youth to continue to utilize the YSO while the DCF investigation is ongoing, and the level of organizational support to the alleged victim and family.

If an incident occurs, your organization should have a process identified ahead of time about if, when, and how to respond to inquiries from the media and the community:

- Identify specific leadership and/or senior staff members as those who should respond to the inquiries. In some organizations large enough to have a communications office, for example, they would be the appropriate ones to respond.

- Remind all other staff members and volunteers to direct inquiries to the designated leader(s), staff member(s), or office.

- Prepare a statement from leadership with information about how children are being protected and how the incident is being handled. Have the statement reviewed by your legal counsel or advisor before being shared with the public.

The CDC* has also suggested the following expanded elements for consideration in these circumstances:

Confidentiality policy

- Withhold the names of potential victims, the accused perpetrator, and the people who made the report to the authorities.

- Decide whether to inform the community that an allegation has been made.

- Ensure that your organization’s confidentiality policy is consistent with state legal requirements.

*Saul J, Audage NC. Preventing Child Sexual Abuse Within Youth-serving Organizations:Getting Started on Policies and Procedures. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2007

Additionally, their task may be to assess the internal conditions or situations that may have allowed the alleged abuse to take place: Were the safety policies and procedures and code of conduct clear enough? Were screening and hiring procedures followed? Was training adequate or inadequate? Were monitoring activities and internal supervisory procedures being followed? When the situation was noticed, how was it addressed?

While this internal process is taking place, it should not interfere in any way with the investigation by DCF or law enforcement. The child or youth should not be interviewed by the internal team. It is also inappropriate to ask victims to tell their stories in front of the alleged abuser. There is a significant difference in power and resources between adults and children/youth, and asking them to relate their story in front of the alleged perpetrator can further victimize them. The best thing for organizations in a situation like this is to cooperate with the investigators and to stay out of their way until the DCF investigative process is completed and the allegations are substantiated or not.

What if the abuse is being perpetrated by another child or youth?

Nationally, it is reported that over one third of reported cases of child sexual abuse are committed by individuals who are under the age of 18 themselves. 8 This can be a difficult issue to address, partly because of the challenge it presents to think of children or youth as capable of sexually abusing other children or youth. In addition, it’s not always easy to tell the difference between normal sexual curiosity and behaviors that are potentially abusive.

First, it is important to distinguish between age appropriate and age inappropriate sexual behaviors. Many children engage in sexual behaviors and show sexual interests throughout their childhood years, even though they have not yet reached puberty. However, normal (or expected) sexual behaviors are usually not overtly sexual, occur between children of about the same age and size, are more exploratory and playful in nature rather than planned, do not show a preoccupation with sexual interactions, and are not hostile, aggressive, or hurtful to the child or to others.

However, these behaviors of childhood and adolescence are of concern when they are extensive or suggest preoccupation, or involve others in ways that are not consensual. That is, sexual behaviors in children present a special concern when they appear as prominent features in a child’s or youth’s life, where there are larger differences in the children’s/youths’ ages and size, when manipulation or bribery are employed, or when sexual play or behaviors are not welcomed by other children/youth involved in the play. This is the point where “play” crosses the line into sexually harmful and aggressive behaviors.

Often, the types of behaviors that “cross the line” can be warning signs that a child or youth has been exposed to, or had contact with, inappropriate sexual activities or material and is reacting to the experience – particularly if the child/youth expresses or demonstrates knowledge of sexual activity that is normally beyond the understanding of others of similar age. Some may have witnessed physical or sexual violence at home and are acting on what they have seen. Some may have been exposed to sexually explicit movies, video games, or other pornographic materials. In other instances, a child or youth may act on a passing impulse with no harmful intent, but may still cause harm to other children/youth. It is always important to seek help promptly in instances of suspected or observed problematic sexual behaviors between children and/or youth.

In these cases, you and your staff should take the following steps:

- If there is reasonable cause to believe that a child/youth has been sexually abused, file a 51A with DCF.

- DCF will screen the 51A Report to determine if a response is warranted.

- Regardless of the outcome of the screening decision, DCF typically makes a DA referral.

- The CACs (Child Advocacy Centers) work collaboratively with the DA offices and will determine their response to these referrals; this could include therapeutic services.

- Problematic sexual behavior (PSB) requires coordinated intervention and services in a number of areas. Children/youth who engage in problematic sexual behaviors with other children/youth need specialized help and support to stop the behavior, and the children/youth who are victimized by those behaviors need help to recover from the trauma. Counseling for the caregivers and the families of the children/youth is also an important component to successfully stop the behavior. Sexual contact between older youth (adolescents) who are close in age carries the additional complexity of appearing “consensual” but nonetheless needs to be addressed.

Massachusetts laws in this area can be confusing, but are evolving and being discussed at senior governmental levels. In most cases, the desired intervention for minors with problematic sexual behaviors is focused on treatment rather than criminal investigation and punishment. Unlike adult offenders, if caught and stopped early, studies report that from 85 to 95% of offending youth never re-offend. 9 10 Thus, early intervention and treatment from a multidisciplinary perspective can be major factors in preventing sexually abusive behavior into adulthood. Only the most serious cases – depending on the age of the child or adolescent who perpetrated the abuse – may result in legal consequences through the juvenile justice system.

Sexual activity between children/youth can be prevented in many of the same ways sexual activity between adults and children/youth is addressed. YSOs must prevent situations where children and youth are alone and unsupervised, both onsite and offsite, and ensure that staff and volunteers are trained in the warning signs and symptoms of sexual abuse. As always, vigilance is key, and staff must be even more vigilant during times when children and youth have been shown to be more vulnerable to abuse: non-structured program time, free time between activities, shower time, trips to the restroom, and changing for the pool or other sporting event, etc. No matter where children or youth are, they must always be there with the knowledge of staff – and always under either staff supervision or observation. Learn more about children and youth with problematic sexual behaviors here: (http://www.ncsby.org/).

Human trafficking and the sexually exploited child/youth

The term Human Trafficking is used by DCF as an umbrella term used to includes two specific types of abuse allegations: Human Trafficking – Sexually Exploited Child, and Human Trafficking – Labor.

Victims of human trafficking in the United States include children and youth, both girls and boys, involved in the sex trade who are coerced or deceived into commercial sex acts, and children and youth forced into different forms of labor or services, for example, as domestic workers held in a home, or farm-workers forced to labor in exchange for shelter or threats of deportation (See Glossary for Definitions).

It has been estimated that between 14,500 and 17,500 people are trafficked into the U.S. from around the world each year. 11 In terms of human trafficking of U.S. citizens within the United States, approximately 244,000 American children and youth are estimated to be at risk of child sexual exploitation, including commercial sexual exploitation. 12 The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children estimates that there are 100,000 youths under the age of 18 already in the commercial sex trade in the U.S. 13 When we talk about Human Trafficking-Sexually Exploited Child, children/youth can be sexually exploited in various places. Examples include the commercial sexual exploitation of boys and girls on the streets or in a private residence, club, hotel, spa, or massage parlor; online commercial sexual exploitation; or through exotic dancing or stripping. Labor trafficking can occur within the agricultural industry, factory, or meatpacking work; construction; domestic labor in a home (e.g., as a Nanny); restaurant/bar work; the illegal drug trade; door-to-door sales, street peddling, or begging; or hair, nail, and beauty salons. Traffickers may target or groom minor victims through social media websites, telephone chat-lines, after-school programs, at shopping malls and bus depots, in clubs, or through friends or acquaintances.

As with child abuse and neglect, there are certain signs and vulnerabilities that children and youth exhibit when they are victims of human trafficking: 14 For male, female, and LGBTQ+ victims, these experiences are similar:

- History of emotional, sexual, or other physical abuse. Children and youth with such a background could fall prey to this form of victimization again;

- History of family domestic violence;

- Family history of addictions;

- Childhood sexual abuse;

- Community violence;

- Loss of loves ones;

- Suicidality within the family;

- Homelessness (particularly for LGBTQ+);

- Truancy;

- Multiple foster home placements;

- History of running away or current status as a runaway. Traffickers know runaways are in a vulnerable situation and target places such as shelters, malls, or bus stations frequented by such children and youth;

- Signs of current physical abuse and/or sexually transmitted diseases. Such signs are indicators of victimization, potentially sex trafficking;

- Inexplicable appearance of expensive gifts, clothing, or other costly items. Traffickers often buy gifts for their victims as a way to build a relationship and earn trust;

- Presence of an older boy- or girlfriend. While they may seem “cool,” older boyfriends are not always the caring men they appear to be;

- Drug addiction. Pimps frequently use drugs to lure and control their victims;

- Withdrawal or lack of interest in previous activities. Due to depression or being forced to spend time with their pimp, victims lose control of their personal lives, and;

- Gang involvement, especially among girls. Girls who are involved in gang activity can be forced into prostitution.

For male, female, and LGBTQ+ children or youth who may be at risk of, or who are victims of human trafficking, these behavioral indicators are similar: shame or disorientation; anxiety; fear; depression; PTSD; suicide attempts; runaway and other oppositional behaviors; self-mutilation; eating disorders; an inability to attend school on a regular basis and/or have unexplained absences; references to frequent travel to other cities; lack of control over their schedule and/or identification or travel documents; are malnourished, deprived of sleep, or inappropriately dressed (based on weather conditions or surroundings); and have coached or rehearsed responses to questions. 15 Children who exhibit these physical and behavioral symptoms must be brought to the immediate attention of DCF as this form of abuse, even though not generally committed by a caregiver, requires mandatory reporting via a 51A for Human Trafficking.

1 The term Human Trafficking is used by Department of Children and Families (DCF) as an umbrella term used to include two specific allegations of abuse: Human Trafficking – Sexually Exploited Child, and Human Trafficking – Labor.

2 Note that for DCF purposes, the term Human Trafficking is an umbrella term used to include two specific allegations of abuse: Human Trafficking – Sexually Exploited Child, and Human Trafficking – Labor. The language above is the MGL definition.

3 (https://malegislature.gov/Laws/GeneralLaws/PartI/TitleXVII/Chapter119/Section51A)

4 Non-mandated reporters may also report suspected abuse anonymously if they choose. Mandated reporters must identify themselves.

5 From the Handbook on Child Safety for Independent School Leaders, by A. Rizzuto and C. Crosson-Tower, Copyright 2012, Reprinted with permission from the National Association of Independent Schools.

6 Crosson-Tower, C. (2003). The Role of Educators in Preventing and Responding to Child Abuse and Neglect. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

7 (http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/gov/departments/dcf/contact-us/dss-directory.html) and (https://www.mass.gov/how-to/report-child-abuse-or-neglect-as-a-mandated-reporter).

8 Snyder, H. N. (2000). Sexual assault of young children as reported to law enforcement: Victim, incident, and offender characteristics. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

9 Przybylski, R. “Effectiveness of Treatment for Juveniles Who Sexually Offend”, Office of Justice Programs (OJP), Sex Offender Management Assessment and Planning Initiative. (https://www.smart.gov/SOMAPI/sec2/ch5_treatment.html)

10 Righthand, S. and Welch, C. (2001) Juveniles Who Have Sexually Offended: “A Review of the Professional Literature. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.” (https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/184739.pdf)

11 U.S. Department of Justice, Report to Congress from Attorney General John Ashcroft on U.S. Government Efforts to Combat Trafficking in Persons in Fiscal Year 2003: 2004

12 Estes, Richard J. and Neil A. Weiner. The Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico. The University of Pennsylvania School of Social Work: 2001. Study funded by the Department of Justice.

13 Polaris Project: (https://polarisproject.org/press-releases/national-human-trafficking-hotline-takes-100000th-call/)

14 National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (2010). The Prostitution of Children in America: A Guide for Parents and Guardians.

15 Human Trafficking Hotline: (https://humantraffickinghotline.org/) and U.S. Department of Education, Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, Office of Safe and Healthy Students, Fact Sheet (2013) Human Trafficking of Children in the United States. (www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/oese/oshs/factsheet.html) and U.S. Department of Justice, Report to Congress from Attorney General John Ashcroft on U.S. Government Efforts to Combat Trafficking in Persons in Fiscal Year 2003: 2004.

- Acknowledgements

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- How to Read This Report

- Mission & Purpose of Taskforce

- A Brief History of How the Taskforce Was Organized

- The Charge of the Legislative Language

- Key Sections

- Section 1: Developing Policies and Procedures for Child Protection

- Section 2: Screening and Background Checks for Selecting Employees and Volunteers

- Section 3: Code of Conduct and Monitoring

- Section 4: Ensuring Safe Physical Environments and Safe Technology

- Section 5: Recognizing, Responding to, and Reporting Allegations and Suspicions of Child Sexual Abuse

- Section 6: Training About Child Sexual Abuse Prevention

- Additional Considerations

- Applying the Framework: A Five-Year Plan

- Appendices

- Section-Specific Appendices

- Downloadable Resources

Take the Pledge to Keep Kids Safe

Join us and commit to learning how you can protect the children you serve.

Sign Up to Access Your Learning Center

Customized child sexual abuse prevention guidelines to meet the unique needs of any organization that serves children.

- Evidence-informed guidance

- Actionable prevention steps

- Keeps track of your progress

- Tailored learning tracks